Nai-furu: The Science of Earthquakes

Earthquake research as an academic discipline in Japan began in the Meiji period. In the early stages of the research, it was foreigners hired by the government who played a central role. After they left Japan, Japanese researchers took over the work and established modern Japanese seismology.

The Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923, which caused terrible damage, was a major turning point for seismology in Japan. Reflecting on previous research policy, new steps forward were taken to break away from it.

In ancient Japan, earthquakes were called "nai," and an earthquake occuring was described as "nai-furu”.

Below, we will distinguish between "earthquakes" as a natural phenomenon and "earthquake disasters" including the damage and secondary disasters resulting from them.

The Dawn of Modern Seismology

Founding of the Seismological Society of Japan

The Yokohama earthquake of February 1880 led to the establishment of the Seismological Society of Japan. The core of the society was led by John Milne (1850-1913), J.A. Ewing (1855-1935), and other foreign teachers and engineers in Tokyo. At the time, research on the Earth's interior structure was being conducted in Europe using seismic waves, but in Japan, where earthquakes were frequent, the focus was on the elucidation of the natural phenomenon of earthquakes themselves. The discovery of two types of seismic waves, known today as P-waves and S-waves, the development of highly accurate seismometers, and other achievements that would later become the foundation of seismology were made.

The Nobi Earthquake and the Theory of Fault Causation

In the 19th century, when the internal structure of the earth was not well understood, the prevailing view was that faults were the result of earthquakes and not their causes. In 1891, a large earthquake occurred in the Nobi region, causing extensive damage. KOTO Bunjiro (1856-1935), who examined the Neodani fault, discovered a huge fault line extending from present-day Gifu Prefecture to Fukui Prefecture, and concluded that the Nobi earthquake was "a landslide slip earthquake caused by a fault".

Establishment of the Earthquake Prevention Research Association and progress of historical research

Following the devastating damage caused by the Nobi Earthquake, the government decided to organize the Society for Earthquake Prevention Research in 1892, based on a proposal by KIKUCHI Dairoku (1855-1917), a member of the Seismological Society of Japan and President of the Imperial University of Science at the time. In addition to SEKIYA Kiyokage, KOTO Bunjiro, NAGAOKA Hantaro (1865-1950), TANAKADATE Aikitsu (1856-1952), and others who had long contributed to seismology, architect TATSUNO Kingo (1854-1919) and others joined the group to conduct historical and statistical surveys on earthquakes and research on earthquake-resistant structures. Around this time, the Seismological Society of Japan was losing its initial momentum due to a succession of foreign members leaving Japan, and it was dissolved, to be succeeded by the Society for Earthquake Prevention and Research.

Historical Records of Earthquakes in Japan

This is a collection of old records on earthquakes and tsunamis in Japan from 416 to 1865. They were utilized after World War II to understand the temporal and geographical distribution of earthquakes, and played a major role in the development of earthquake and volcanic eruption prediction.

大日本地震史料 増訂第1巻

It was greatly enlarged by MUSHA Kin’kichi (1891-1962) during the Showa period (1926-1989) and published as Volumes 1-3 of the Revised Historical Documents on Earthquakes in Japan.

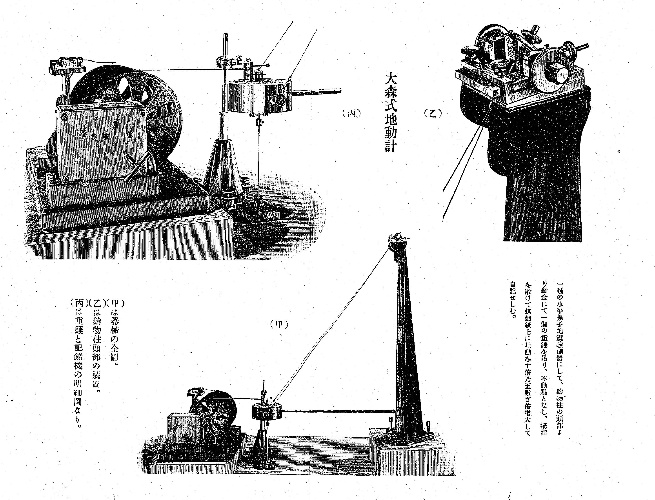

Omori Seismology

In 1897, OMORI Fusakichi (1868-1923) was appointed secretary of the Society for Earthquake Prevention and Research. From then until the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923, Omori was an authority on seismology and worked tirelessly on research. It is said that most of the voluminous reports of the Investigative Committee were written by Omori, the secretary of the committee. For this reason, seismology during this period is often referred to as "Omori seismology".

IMAMURA Akitsune (1870-1948), who was active during the same period, was three years younger than Omori and is said to have been inspired by the Nobi earthquake to pursue seismic research. Although he had to remain an associate professor for more than 20 years until Omori's sudden death shortly after the Great Kanto Earthquake, he was passionate about earthquake prediction and left behind achievements that are still highly regarded today, including research and studies on the relationship between topographical changes and the occurrence of earthquakes.

Achievements of Geophysicist SHIDA Toshi

SHIDA Toshi (1876-1936) laid the foundation of geophysics. From the vast number of papers published in Reports of the Earthquake Prevention Research Committee, he discovered that there are two types of seismic waves that first reach the observation points: those that move toward the epicenter and those that move away from it, and that the distribution of the points where these two types of waves are observed is regular. In 1929, he received the Imperial Prize of the Japan Academy for his many years of achievements.

Tokyo Earthquake Warning Commotion (OMORI Fusakichi vs. IMAMURA Akitsune)

In September 1905, IMAMURA Akitsune published an article in the magazine Taiyo titled "A Simple Method to Mitigate the Damage to Lives and Property Caused by Earthquakes in Urban Areas". In the article, Imamura wrote, "In the Edo period, a major earthquake that killed more than 1,000 people occurred on average once every hundred years, and since 50 years have passed since the most recent earthquake in 1855, there may be some time left before the next major earthquake occurs, but if there is an example like the Genroku earthquake in 1703, 54 years after the 1649 earthquake, then we should not postpone disaster prevention even for a day," he said, predicting the damage that would occur if a major earthquake struck Tokyo at that time.

This was sensationalized in an article titled "The theory of a major earthquake - prediction of a major disaster in Tokyo" in the Tokyo Niroku Shimbun on January 16, 1906, and combined with the popular belief that "there are many fires in the year of the fire horse," it caused anxiety among the public.

OMORI Fusakichi, an authority on seismology at the time, published an article titled "Tokyo and the Baseless Theory of a Major Earthquake" in the magazine Taiyo in March of that year in order to calm the fuss. Imamura was rather dissatisfied with this article.

17 years later, in 1923, the Great Kanto Earthquake struck, and shortly afterward Omori died. Imamura wrote "The Conquest of Earthquakes" in 1926, in which he reiterated the validity of his own damage estimates from 20 years earlier and his abiding belief in earthquake prediction and prevention.

While the series of debates helped in no small measure to disseminate to the public the results of seismology up to that time and knowledge about prevention, they also highlighted the limitations of seismological research at the time.

The Impact of the Great Kanto Earthquake, and Aftermath

The Great Kanto Earthquake of September 1, 1923 was a massive earthquake with a magnitude of 7.9 on the Richter scale. Because the earthquake occurred just before noon, fires broke out in homes and restaurants where people were preparing for lunch, resulting in an unprecedented total of approximately 105,000 deaths. It is estimated that 90% of the victims were lost in the fires.

Earthquake Prevention Research Association

This is a record of the Great Kanto Earthquake investigation by the Earthquake Prevention Research Association. It contains many photographs and diagrams, and consists of five volumes: Earthquakes and Tsunamis, Earthquakes, Buildings, Structures Other Than Buildings, and Fires. Many analyses based on geophysical perspectives, which had not been considered important before, are included in the report.

In 1925, when the report was issued, the Earthquake Research Institute was established and the Earthquake Prevention Research Institute was dissolved.

Reflections on and Conversion to Conventional Seismology

When the Great Kanto Earthquake occurred, Omori was on a business trip to Sydney and learned of the occurrence from the records of a local seismological observatory. He hurriedly returned to Japan, but his illness worsened and he soon passed away. The seismology he developed during the Meiji and Taisho periods focused on statistics and earthquake measurements. Although the value of the records he produced was not small for earthquake research, the general public became dissatisfied with seismology's failure to predict the Great Kanto earthquake. The academic community was keenly aware of the need to pursue earthquakes as a natural phenomenon from a geophysical perspective, which had been lacking, to further research related to earthquake disaster prevention, and to train young researchers.

NAGAOKA Hantaro, Direction of Earthquake Research

Nagaoka, a physicist, had long advocated for earthquake research from a geological and physical perspective, but this was never accepted by the seismological community before the earthquake. In this paper, he sharply criticizes the old seismology and states that the research direction should be reconsidered.

Establishment of the Earthquake Research Institute

In November 1925, the Earthquake Research Institute was established on the campus of Tokyo Imperial University. The core members were SUEHIRO Kyoji (1877-1932), an engineer, and TERADA Torahiko (1878-1935), a physicist and scholar of literature. At the Earthquake Research Institute, the emphasis was on basic seismological research and earthquake disaster prevention, with authorities in science and engineering from across the country serving as principals, providing research opportunities for young people one after another. The Central Meteorological Observatory also strengthened earthquake observation using the Wiechelt seismograph and promoted research on earthquakes from a physical standpoint. In addition, the Department of Seismology was newly established at Tokyo Imperial University, and earthquake research was also deepened at Kyoto Imperial University and Tohoku Imperial University.

After the earthquake, IMAMURA Akitsune made a distinction between earthquakes, which are natural phenomena beyond human control, and earthquake disasters, which can be prevented through human efforts, and developed disaster prevention measures. TERADA Torahiko, who was active in a wide range of research fields, also had a strong interest in disaster prevention and commented on a variety of disasters, not limited to earthquakes. The term "bosai” (Japanese for disaster prevention) was coined by Terada.