Introduction to Natural History Materials

Fauna and Flora in Illustrations: Natural History of the Edo era

Introduction to Natural History Materials

1. A plethora of manuscripts

Illustrated encyclopedias during the Edo period, especially those that included animals, often included material that was copied from manuscripts published by others. In fact, not just pictures but also annotations and the dates of the originals were commonly transcribed. It is important to bear this fact in mind, lest one mistake a manuscript for an original work and misjudge an artist’s skill or misidentify the dates of his career. It is also important to understand that transcription was not considered plagiarism. Prior to the invention of photography, flora and fauna were most reliably identified from hand-drawn illustrations. And given the high cost of publishing an illustrated encyclopedia, very often the on practicable way to have information on hand was to make a transcription.

For instance, although there are slight differences in shape, these four pictures of a female smew (wild duck) are quite similar. This is because there were all transcribed from a picture found in Shukin gafu (衆禽画譜) edited by MATSUDAIRA Yoritaka (松平頼恭), the feudal lord of the Takamatsu domain, in present day Kagawa Prefecture.

『奇鳥生写図』<本別10-38> 狐アイサ

『錦窠禽譜』冊5 <寄別11-10> 狐アイサ

『水禽譜』<本別10-21> 狐アイサ

『張州雑志』巻13(名古屋市蓬左文庫蔵)赤アイサ

2. Quality of manuscript

Yakuho zusan (薬圃図纂), authored by HATTORI Noritada (服部範忠) in 1726, includes illustrations of flora mentioned in Chinese poetry, and its content comprises transcribed manuscripts. The following four pictures are of a chestnut bur. Some of them are skillfully copied, but others are not. For example, it is difficult to know precisely what Figure 3 and Figure 4 were originally. Manuscripts will differ according to the skill of the transcriber, so when studying a manuscript, it is important to survey as many other similar materials as possible. For example, the title of Figure 1 differs from the others, but the contents are the same.

『花葉形状図説』<特1-450>

『薬圃図纂』<232-240>

『薬圃図纂』<特7-242>

『薬圃図纂』<特1-344>

3. Difference in coloration

Even when printed from the same printing block, different copies of the same print can exhibit differences in coloration depending on when they were printed, and mistakes in judgment are possible if only one copy of a print is available for consideration. For example, shown below are two different versions of Suizoku shashin tai no bu(水族写真鯛部)by OKUKURA Gyosen (奥倉魚仙); which was published three times in 1855, 1856, and 1857. Figure 1, published in 1855, has proper coloration, but the colors of Figure 2, published in 1857, are quite bright compared to Figure 1. As mentioned, it is necessary to always examine several different copies when evaluating a particular work.

安政2年 (1855) 本<特7-151>

安政4年 (1857) 本<特7-152>

4. Instances of corrections and deletions

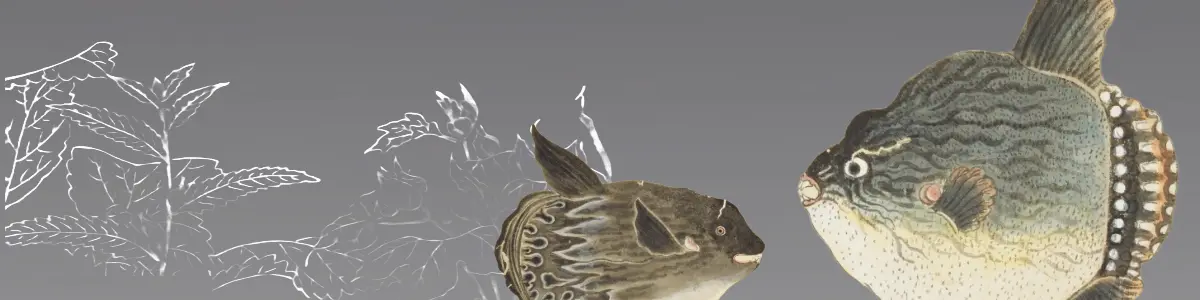

These three prints include the same pictures of a globefish but differ in several points. There are more than a few cases like these.

『龍の宮津子』享和2(1802)刊 <108-227>

『魚貝譜』<166-181>

『魚貝略画式』<241-102>

5. Books with different titles but the same content

There are many instances of manuscript books that were given have a different title from the original by the transcriber. It is easy to mistake such titles as unrelated unless you pay close attention to the content.

For example, Chosho anshi (鳥賞案子) has a preface written in 1802 and was authored by HINO Kanroku, who was in charge of bird breeding for the Satsuma domain, located in modern-day Kagoshima Prefecture. It was one of the most widely referred to books on bird breeding during the Edo period and there are numerous known transcriptions. The three books listed below have different titles but all have the same content. Additionally, there are at least 10 other known variations of this manuscript.

『鳥賞案子』<特1-1716>

『飼鳥必用』<237-45>

『鳥はかせ』<特1-924>

鳥賞案子 3巻 [3]

飼鳥必用 3巻

鳥はかせ

Natural History during the Edo period

Natural history during the Edo period was based on traditional Chinese pharmacology (本草, bencao in Chinese, honzo in Japanese) and horticulture. There are several characteristics that distinguish the development of natural history in Japan from that in China. Here, we summarize four major points.

① Flora and fauna of Japanese origin

Chinese pharmacology books were first introduced to Japan during the 6th century, when it was assumed that the same animals and plants inhabited both countries. The development of foreign trade during the Azuchi–Momoyama period led more and more Japanese to travel abroad, and as they did, differences in name or shape between Japanese and foreign breeds became widely recognized. As a result, natural history writers during the Edo period tended to focus on animals and plants that were indigenous to Japan.

② The development of horticulture and the contribution of plantsmen

During the Edo period, horticulture became popular across all social classes, from the Shogun to ordinary city folk. What is more, it reached new heights despite developing differently than in either China or Europe. From the middle of the Edo period, many books on horticulture appeared and even books on natural history mentioned horticultural plants. In addition, plantsmen went deep into the wilderness and brought back a good deal of scholarly knowledge that was useful in horticulture. In many cases, plantsmen created garden that they opened not just to other naturalists but to the general public, just like modern botanical gardens. There are even records of Shoguns visiting plantsmen.

③ A wide range of descriptions

Modern books on animals and vegetation concentrate on describing morphology and physiology. Natural history books published during the Edo period, however, are characterized the wide range of information that they included. For example, these materials often included common names in different regions (dialects); common usages such as for wooden printing blocks or as ingredients in paper-making; taste and pharmacological effects, the catching and breeding of birds, or the cultivation of plants. Sometimes they even quoted classics, such as Man’yoshu and Makura no sōshi, or included haiku and Chinese poetry. They even included cultural aspects, such as popular places to find bush clover or fireflies, famous cherry trees or camellia gardens, and even the origin, history, and children’s games relating to certain plants. In Europe, natural history developed as a branch of science that focused on objective description. In contrast to this, naturalists in Edo-period Japan kept a human point of view that included cultural factors, and this tendency seems to have gradually grown stronger.

④ Authors from varied backgrounds

Until the Muromachi era, books on natural history were written primarily by doctors or botanists. In contrast to this, during the Edo period, rather than a handful of specialists, these books were written by people from a wide variety of backgrounds, including aristocrats, samurai, doctors, intellectuals, painters, merchants, craftsmen, gardeners, farmers, Buddhist monks, and Shinto priests. Thus, during the Edo period, naturalists often interacted with colleagues from other social classes, and it would not be unusual to see aristocrats, intellectuals, and merchants all in one place, discussing their latest discoveries.